UNDERSTANDING A DIFFICULT PAST by Gail Robyn Safian

- ellencdonker

- May 1, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: May 6, 2020

A community celebrates African American history and freedom

Revisiting history is important. It helps us understand our past as well as our present, so we can learn from our errors. Last spring, the Durand-Hedden House, Maplewood’s historic house museum, which strives to educate the public about local and regional history, decided to complement an upcoming “Juneteenth” celebration with an in-depth exhibit on the history of slavery in New Jersey. It was most timely, considering that 2019 was the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved African people in America. It was also a surprising revelation to researchers and viewers alike.

Juneteenth, sometimes known as “Freedom Day” or “Emancipation Day,” is a contraction of the words “June Nineteenth.” It commemorates the belated announcement on June 19, 1865, of the abolition of slavery in the state of Texas, 18 months after the Emancipation Proclamation, and five months after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States. The celebrations that followed began a tradition that has lasted for 155 years, marked by annual events across the country.

Interested in hosting a celebration of African American history and freedom for our local communities, the Durand-Hedden House joined with the South Orange/Maplewood Community Coalition on Race and museum consultant Claudia Ocello of Museum Partners. The event, held last year at Durand-Hedden and its surrounding Grasmere Park, featured an array of children’s activities, displays by The Nubian Heritage Quilter Guild, reenactors of the 6th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops and friends, and performances by the Columbia High School Special Dance Company and the Kamate Traders, African drummers and dancers. The SOMA League of Women Voters offered voter registration forms, and the Maplewood Health Department performed health screenings.

The gathering was one of the largest Durand-Hedden has held. And it fulfilled the intention to be reflective of the community. More than half of the 250 people who attended identified themselves as African American or multiracial. Although Durand-Hedden has presented many Black History programs in the past, such as a Harriet Tubman reenactor and a presentation by the late Giles Wright on New Jersey and the Underground Railroad, the museum wanted to reach for a deeper, richer connectedness. With the help of the Coalition, this goal was realized. It was planned for presentation again this June but will be rescheduled due to public-health concerns.

Delving into New Jersey’s Troubled History

Although most people associate slavery in America with the South, people of color were enslaved in New Jersey from the late 1600s, by the first Dutch and English settlers, until the end of the Civil War.

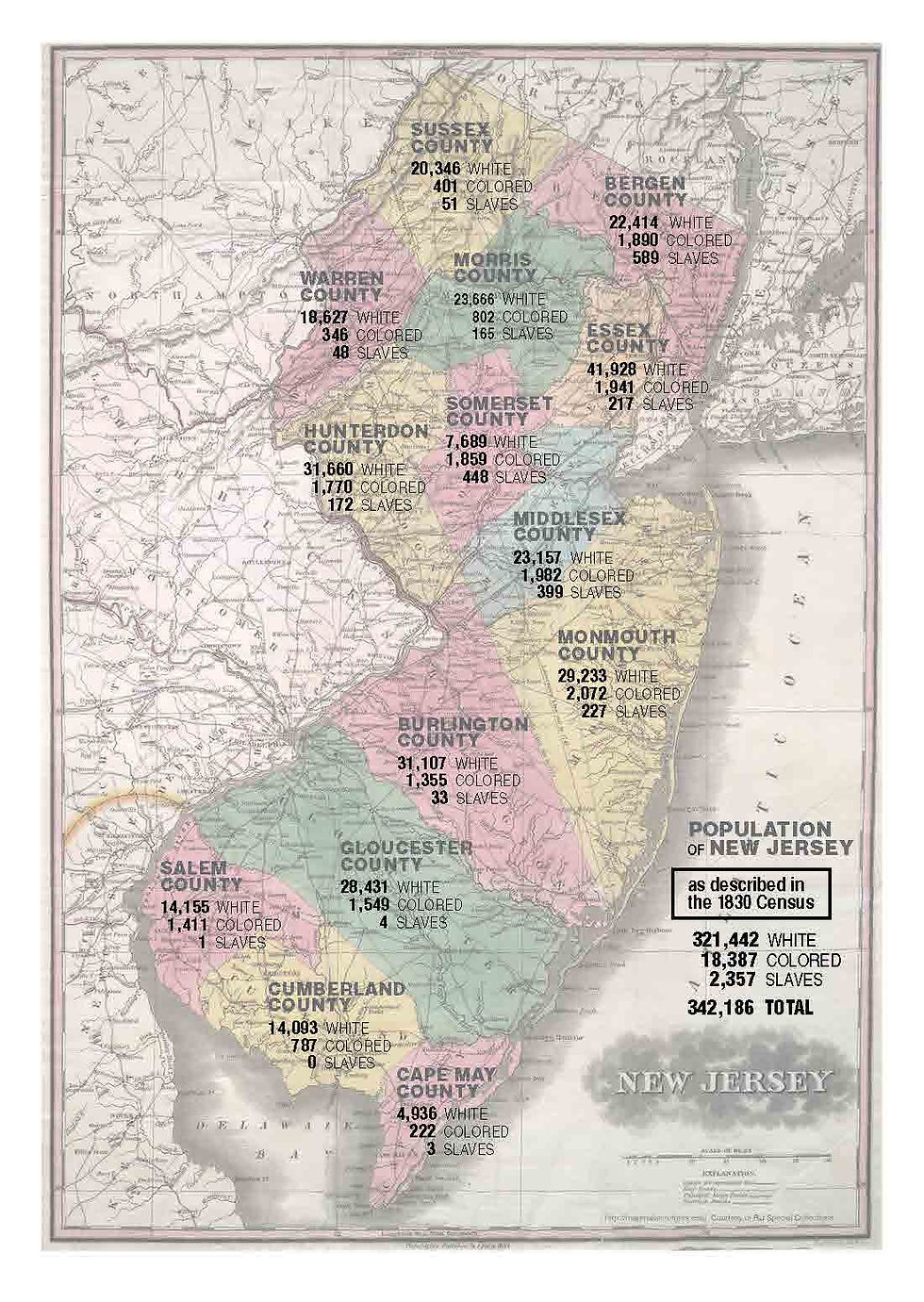

The state’s gradual abolition act of 1804 freed children born of enslaved women after July 4 of that year – but only after a period of indentured servitude of 25 years (for males) or 21 years (for females). The 1830 census recorded about 2,300 enslaved people in New Jersey, more than 200 of them in Essex County. An 1846 law changed the title, but not the status, of enslaved people born before July 1804, making them indentured servants who were “apprentices for life.”

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, many enslaved people took freedom into their own hands. They escaped to New Jersey from bondage in the South, and they escaped from bondage in New Jersey, chased by slavecatchers, to freedom in Canada. Their stories are testaments to immense courage and resilience.

The last 16 elderly “apprentices” in New Jersey were not freed until Jan. 31, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment legally ended slavery throughout the United States. New Jersey was the last northern state to ratify that amendment, and that was not until 1866, after it had already become law. It was a whimpering end to decades of battles between abolitionists and those who would build their wealth through racialized exploitation.

Barbara Velazquez, a trustee of both the Coalition and SOMA Action, was part of the research team. “I found doing research on enslaved and free African Americans in the Maplewood-South Orange area to be enlightening,” she said. “In some cases, it was as though I had a window into their lives as I followed them from census year to census year. I had naively believed that African Americans here enjoyed a much better life than their enslaved brethren in the South, but I learned that, sadly, this was far from the truth. The life of African Americans in New Jersey was as fraught with danger; the difference was of degree, not of kind.”

For all involved at Durand-Hedden and the Coalition, this history was a revelation. Audrey Rowe, program director of the Coalition, commented, “It was so gratifying last year to learn and to share with the community the many uncommonly known details about our local experiences with slavery.”

Another Perspective on African Americans: The Battle for Women’s Suffrage

The next major exhibit at Durand-Hedden explores the stories of women in New Jersey and across the nation who fought for women’s suffrage. The program was scheduled for May but will be postponed to the fall due to the coronavirus pandemic. Race also played a role in the battle for women’s suffrage. Both before and after the Civil War, African American women had to struggle not only with the entrenched sexism faced by white women, but also with racism. This exhibit, too, will bring surprises to viewers, as research revealed the thousands of unheralded African American suffragists who campaigned, raised money, participated in protest marches, and petitioned state and federal legislatures for women’s right to vote, the right to have a voice in the running of this country and in the making of its laws.

Among New Jersey’s suffrage leaders was Florence Spearing Randolph, who became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. As an organizer and public speaker for the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Rev. Randolph was an outspoken critic of racism and sexism.

Rev. Randolph also was a leader in the African American women’s club movement, a potent force for helping women of color improve their lives and communities, and as an advocate for votes for women. In 1915, she helped to organize the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. On behalf of the federation, she appealed directly to President Woodrow Wilson, asking him to address the issues of race rioting, sexual assault of Black women, and lynching, which took the lives of more than 4,000 African Americans across twenty states between 1877 and 1950.

The Fight Goes On

Even after the abolition of slavery and the passage of federal amendments that gave first Black men and then (after 50 years) all women the vote, the struggle for equality continues. Almost 100 years later, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was required to remove the legal barriers that states (not only in the South) had erected to keep African Americans and immigrants from voting. And yet voter suppression, in various ways, continues in some states. Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.

For more information about Durand-Hedden programs and a link to the History of Slavery in New Jersey exhibit, visit durandhedden.org.

Gail Robyn Safian has lived in Maplewood with her family for many years, and is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Durand-Hedden House. She enjoys researching and writing about history.

Thank~you all for this work, and educating so many of us who did not know about the History of Slavery in New Jersey!

Amélie