FINDING HOME BY THE TRACKS By Joy Yagid

- Joy Yagid

- Jun 14, 2024

- 5 min read

A Brooklyn couple’s journey to Maplewood with history and hauntings

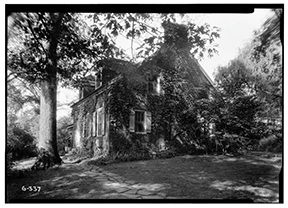

Scott and Sonya Selig live in one of the oldest homes in Maplewood. At approximately 300 years old, it stands tucked hard against the train tracks, facing the wrong way at 22 Jefferson Avenue.

Known as the Montgomery Ogden House in the Library of Congress’ listing for Historic American Buildings Survey, it is one of two homes in Maplewood surveyed during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. The Timothy Ball house, where legend has it that George Washington slept, is the second.

The Seligs view themselves as stewards of this important home, but that wasn’t their plan in 2007 when they moved here from Brooklyn.

After realizing that navigating the New York City school system was not for the faint of heart, they followed friends who followed friends to Maplewood. They rented on Dunnell Road while they looked for a home to buy.

Sonya wanted a new ranch home, like one in the Newstead neighborhood of South Orange. “Let’s get one of the modern ones because I’m from California,” Sonya said. “I was used to one story.”

Scott visited the Montgomery Ogden House, also known as the Old Stone House, around the corner from where they rented, for each of its three open houses. He was sold on it. Sonya needed a bit more convincing.

“A big part of it is because it’s old,” Scott says. “It has a coziness.”

He adds that it’s just big enough for their family and met all their criteria, even accommodating their goal to be a one-car family. The house is walking distance to their childrens’ schools, to town and to the train, which is right outside their windows.

The home faces the tracks because it was a stop on what would become the Morris and Essex line. According to the Maplewood Historic Preservation Commission’s report on the Old Stone House, it was known as the Old Stone House Station from 1838 to 1856, a flag stop on the train line when Maplewood was known as Jefferson Village. A flag stop meant you waved a flag at the train when you wanted it to stop. You bought tickets in the waiting room, which was a small general store that Betsy Durand, sister of Asher Durand, the famous painter and Maplewoodian, ran from what used to be the kitchen.

Scott finally got Sonya to come to the last open house. By this time, the price had dropped by $100,000. She walked in and looked up the stairs. “I imagined my daughter walking down those stairs in a prom dress, and that was it. It was home,” she says. Sonya also loved the dining room’s massive fireplace.

The house's foyer looks much the same as it did in 1936. (T) Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS NJ-337, Library of Congress, John Spinola, Photographer (Nov. 6, 1936). (B) Photo by Joy Yagid.

In spring of 2010, the Seligs bought the home. The timing coincided with the Maplewood Historical Commission designating it as an historic home. That meant it would come with a list of what they could and couldn’t do to it. Scott says it did not scare them away from buying the house. “Eventually we determined that no, we liked the house enough to work with it.”

As the Seligs found out, owning an historic home is not easy. The couple scoured the internet and spoke with historical experts for sources and recommendations. They worked with an architect to inspect it and create a punch list of items that needed to be completed. Although he deemed the house to be in remarkably good shape, he noted that one of the support beams, a bark-covered tree trunk in the basement, had old termite damage.

Then and now. (T) Courtesy of the Seligs. (B) Photo by Joy Yagid.

The architect came to believe that the original part of the home was of Dutch construction. Sonya describes that when he found parts of the original structure, including probably the original shingles, “he came downstairs so giddy and said, ‘This is Dutch construction. This is Dutch!’” She says, “In his best estimate, the original part of the house could date between 1710 to 1720, but there’s no way to know for sure. This means it could have been built by Dutch owners before the English came or built by Dutch people hired by English owners.

Luckily, the Seligs learned that the termite-damaged beam in the basement could be shored up. Next, the chimney took its place as the top priority when it started leaking during heavy rains. Sonya has even seen a snowflake or two come down the chimney. They located a mason who will repair it in an historically accurate way.

There are some things for which to be grateful, such as having 18-inch-thick stone walls during Superstorm Sandy. “The house is solid though. I never felt safer,” Sonya says. “One of the giant maples’ trunks snapped and smashed against the house and broke in half and went into the ground. There was no damage.”

Of course, having an old house involves more than just fixing and repairing things in an historically accurate way. They can also have ghosts. Yes, the Seligs say that their home is haunted by several ghosts, but believe they’re the friendly type. One may even be a prankster.

The prankster made itself known shortly after they moved in. Sonya’s mom came out to help and was standing in the dining room unwrapping glassware. Sonya was in the hallway making a mess of unrolling a sticky pad for the rug. She says, “And she’s standing there … and her pants went right to her ankles for no reason. They just flew. It wasn’t like they slid down. They went down to her ankles … and then we both just started laughing!”

The Durand Hedden House brought in a medium to The Old Stone House prior to their 2016 Halloween event about haunted houses. He brought an EMP device to see whether there was any activity. Sonya recalls that the device was “going bonkers” but only when they asked questions. So they stuck to yes-or-no questions, and the ghost responded accordingly. It was a woman who told them that there used to be orchards, that she lived in this house, and that she worked on the land. The tax rolls indicate that there was at least one enslaved person, but they didn’t know whether she was the woman they were talking to.

During the course of almost 200 years, three Durands have lived at the home. Betsy Durand, sister of Asher Durand, lived there with her husband, Daniel Beach from 1837 to 1864. Betsy operated the Clinton Valley Store out of the old kitchen during the time when the house was used as a train station. Asher lived there next, followed by Frederick.

The home has been modified over the years, and the grounds have changed too. The train tracks were eventually elevated and the garage is now gone. Several years ago, the Seligs renovated the back yard and added beautiful gardens to complement the home’s historic character. They continue to make this old house their home.

Scott says, “[We] will take care of it and make sure it can continue to be viable as a house in the modern times.”

Joy Yagid is a local photographer and gardener who learned to knit on the train while she commuted. She didn’t know the Seligs at that time, but if she had, she would have waved.

Comments