Everybody Loves Judi

- ellencdonker

- Feb 1, 2019

- 6 min read

Columbia High School counselor retires from a career helping kids, by Ellen Donker

Anyone who spent time in Judi Cohen’s office remembers it as a place where kids came first. No matter that the door was opened and knocked on multiple times. The phone rang. And the intercom was apt to buzz with announcements while emails poured in. Her focus was completely on the person sitting across from her.

For nearly 30 years as the Student Assistance Counselor (SAC) at Columbia High School, Cohen made a career of helping youth navigate the problems of life, both big and small. Now, after 44 years working in the South Orange Maplewood school district, she has retired.

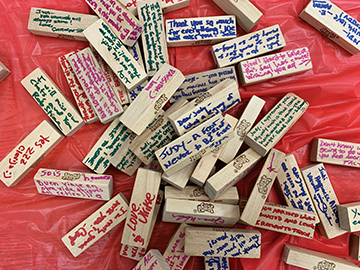

Cohen was recently feted with a going away party in the school library that drew over a hundred of her co-workers, family and friends, with some traveling from as far away as Massachusetts. She is clearly a legend among students and peers, revered for her unwavering dedication to children.

Michael Loupis, trained by Cohen as a SAC, says of her influence, “What I love about Judi is that she always put the students and families first. From the minute you entered the office with Judi until the minute you left, she allowed you to be heard…[and] always found a way to help you resolve any issue you were going through.”

Cohen reflects on a lifetime spent in the South Orange Maplewood school district and clearly sees it as a good run that, given the chance, she’d repeat in a second life. Growing up in South Orange, she started her education at the Marshall School, attended South Orange Junior High followed by Columbia High School.

She admits that her memories of home are from a bygone era. Surrounded by a loving family, she had grandparents who lived nearby, an aunt and uncle across the street and another set of relatives in Maplewood. Her father ran a hardware store in the Vailsburg section of Newark and closed the store from 6 to 7 p.m. so he could be home with his family for dinner. She thrived on these tight family bonds.

Earning a B.A. in speech and English from Case Western Reserve University, Cohen returned home to work as a permanent substitute four days a week at New Brunswick High School. On her day off, she subbed at South Orange Junior High which, at the time, included grades 6 - 9. Six weeks later, she was offered a position there when an English teacher retired.

Eventually, Cohen moved to the high school as a result of Columbia’s transition to include the 9th grade class. There she taught English as well as research and debate for juniors and seniors. She recalls, “That was the best of the best. I just loved it.”

Over time, though, she realized that “all these kids are constantly writing me their problems, sitting with me during my lunch…and it was so much counseling. So I said this is crazy. Why don’t I just get an office.”

That spurred her to enroll at Montclair State University, where she earned a degree in guidance and counseling as well as certifications to be a student assistance counselor (also called a substance abuse counselor) and a supervisor. When the position of Student Assistance Counselor opened up at Columbia High School, she accepted it with trepidation, afraid she was leaving behind the best job she’d ever had. She’s never turned back.

With a personality larger than life, Cohen would greet students with a ‘Hi Love’ or ‘Hey Handsome’. She says, “I’m not formal and I think that helps. If you’re too formal, kids can’t relate. The name of the game in this job is building relationships, building trust.”

Typically, students ended up in her office by word of mouth. “Kids refer kids to me, would you believe it?” Cohen also got referrals from security, guidance, the main office, really anyone. And she made it her business to be involved with clubs, attend games, and strike up conversations in the cafeteria. She says, “You can’t hide in this job.”

When Cohen started out in 1990, much of her work involved student assistance for substance abuse. She remembers kids throwing wild parties when their parents weren’t home and the police getting called. More recently, the partying has been supplanted by mental health issues with kids using marijuana and alcohol to self-medicate.

Cohen sums it up, “Kids haven’t learned to cope. The sense of family is not like what it was yesteryear.” She attributes much of it to the financial pressures families face, necessitating that two parents work full-time. Combined with running a household – getting dinner on the table, making sure homework is done and attending to all the other to-do’s on the list – parents are exhausted and sometimes lose sight of what their children need.

Cohen also saw the trend of parents swooping in to fix things for their children rather than teaching them to advocate for themselves.

When students came to her office with a problem, she’d often say, “Let’s talk about life. Put it into some perspective.” Then she’d help them determine how to solve it.

She says that most kids aren’t planners so she’d counsel, “Be logical. Would you ever stop watching a movie in the middle? Play out some of your plans in your head. See where it goes instead of stopping in the middle, getting frustrated, getting anxious, wanting to kill yourself.” By coming up with a talking plan and practicing it with Cohen, students were better prepared to resolve issues on their own.

Cohen laughs about her ability to help kids solve problems. “It’s not because I’m so terrific. It’s because I’m so old. I’ve lived. I get it.”

Fallyn Balassone, who worked with Cohen for nine years, sees it like this, “Judi can be really direct in a way that students love and really respond to, and in a way that other professionals fear talking to kids. I don’t think she operates from a place of fear, just straight from her heart.”

Cohen likens the job to an emergency room of a hospital, saying, “I don’t know what’s coming in, but I’d better be prepared.” Her day could include the re-entry of a student recovering from a suicide attempt; a child locked out of his home by a mentally ill parent; a girl who wouldn't attend gym because she couldn't bear to change her clothes in front of others (solution: Cohen gave her a drawer in her office to store her clothes along with privacy to change); and a student who stopped attending a class because she couldn’t face seeing the boyfriend who had broken up with her.

Certainly, this type of work takes its toll because, as Cohen says, “there’s not a lesson plan.” Her husband of 40-plus years helped her decompress. She watched a lot of TV to take a break from talking. And her friends helped her process the difficult stories she heard. “Faith helps as well.”

Besides her professional qualifications, Cohen believes that her years of experience in the classroom made a difference because she knew what teachers and kids needed. Beyond that, she says, “It comes naturally to me. Don’t ask me to handle the phone. I hate technology.”

With such a lengthy career, many viewed Cohen as a fixture. But she explains, “I’m tired. I think I’m getting burned out doing this for so many years. There also comes a time – it’s something that comes over you – to give it up to someone else.” She notes, “You’ve really got to be into their [students’] world. You’ve got to know their music, their trends, their styles.”

Cohen looks forward to traveling with her husband, who is thrilled they no longer have to conform to a school calendar. They’ve already booked a trip to South America in March, and plan to visit Dallas more frequently to see their grandchildren.

She also wants to audit courses in history and art, and possibly to work with dogs in a shelter.

In the end, though, Cohen notes, “I’m fortified by kids. That’s the only thing about retirement that scares me.” Chances are, wherever she goes, she’ll seek out youth and find new opportunities to engage with them.

Ellen Donker appreciates the morning spent in Judi Cohen’s office, seeing her in action. By the end she felt as if she had made a good friend, a testament to Cohen’s innate ability to connect.

Comments